Content warning: this piece mentions illness, hospitalisation and death.

On triage:

Upon arriving at a hospital emergency department, you are asked to describe your problem. Whether you have a broken leg, or chest pain, or burns so severe you can hardly breathe, your problem must first be described before it can be treated.

This process is called triage.

Medical students – and fans of Grey’s Anatomy – are taught that an important component of triage is patient history. What comorbidities does the patient have? Are there other factors at play? What else might not be visible, but is key to fixing this patient’s problem?

Sometimes, the most important considerations are those which are not immediately obvious.

On disappointment:

Earlier this year I was hospitalised with a kidney infection. It wasn’t life-threatening, but serious enough to land me an overnight stay in hospital. I took a week off work while I recovered.

My body had been poked and prodded and pumped with antibiotics and narcotics, all of which left me tired, exhausted. Yet using a week of sick leave – which I had earned, and was entitled to – felt like an admission of failure. I felt guilty for underperforming at work, for taking time off during a busy project. I was frustrated, ashamed even. My body had let me down, and I in turn had let down those around me.

At least, that’s the narrative I told myself.

On duality:

We can always learn from what a problem is not. There’s a reason hospital patients are subjected to various blood tests and CT scans and ultrasounds: rule out the most serious of concerns, and then go from there. A negative test result can lead doctors to the underlying problem; the answers are often found in the inverse.

In his extensive work on narrative therapy and practice, Australian social worker and eminent narrative therapist Michael White implemented a similar principle. He wrote that “in order to express one’s experiences of life, one must distinguish this experience from what it is not” (White 2005, p. 15). In paying close attention to the inverse, or opposite, of a person’s experience, we can better understand the experience itself.

White referred to this conceptual framework as ‘the absent but implicit’ (White 2000, p. 41).

In analysing the retelling of an event, or an encounter – as told to ourselves, or by others – we must closely examine what is missing or unstated in that retelling. This practice of ‘double listening’ helps us explore the duality of storytelling, and uncover the hidden aspects of a person’s experience (Freedman 2012, p. 2; White 2000, p. 41; 2003, p. 30). This process formed the foundation of White’s narrative therapy practice, for which he was internationally renowned.

This duality mirrors the work of poststructuralist writer and philosopher, Jacques Derrida, who greatly influenced White’s interest in the absent but implicit (Freedman 2012, p. 2; White 2003, p. 31; 2005, p. 15). Derrida explored the duality of affirmation and negation present in negative theology, which was of course influenced by Freud’s theory of negation (Freud Museum London 2016; Lawlor 2019). For those interested in learning more about Derrida and his work, I recommend his entry in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Lawlor 2019).

On mapping:

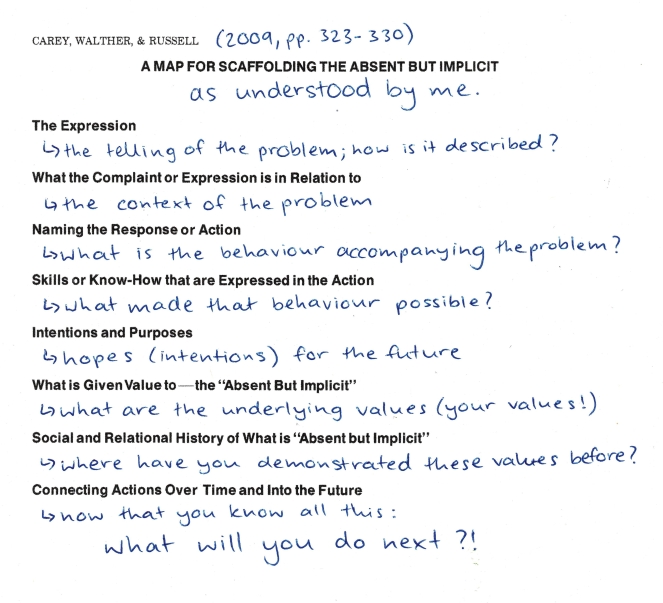

Sadly, Michael White died in 2008. But his legacy lives on in other writers and researchers interested in narrative practice and therapy (Dulwich Centre Publications 2020b). In 2009, Maggie Carey, Sarah Walther and Shona Russell released a review of White’s ideas on the absent but implicit. Building on White’s preliminary mapping of the concept, they proposed a scaffold for using the absent but implicit in narrative therapy (Carey, Walther & Russell 2009, pp. 323-330).

This scaffold is shown below.

For accessibility purposes, you can download a transcript of the above annotations here.

Essentially, this is a conversational roadmap for narrative therapists. However, it is also a useful tool for those interested in uncovering their personal and professional values, too often excluded from our surface-level narratives (Carey, Walther & Russell 2009, pp. 320-321).

The story about my kidney infection is one such narrative.

On narrative expression:

Following my hospitalisation, I returned to work one week later (which, as it happened, was my last week in the office before remote working became the new normal). The big project I had so anxiously left behind was eventually completed, and my manager made it abundantly clear that she was more concerned with my health than any lost productivity.

So why was I so worried about taking time off?

“I felt guilty for underperforming at work.” This is my expression of the problem, as seen through the lens of the absent but implicit (Carey, Walther & Russell 2009, pp. 323-324). I didn’t want to let anyone down, least of all at my place of work.

If we invert my problem, we begin to see the implicit meaning: that I value diligence and commitment. I see things through. What seems fairly obvious now is that I normally consider myself a diligent employee and colleague, and my illness – however temporary – challenged this self-perception. The guilt and frustration I experienced were evidence of this.

My values weren’t just revealed by this narrative; they were its cornerstones from the beginning.

On values:

If I was undergoing narrative therapy, my next – and final – step would be consolidating these newfound values with my future behaviour. Carey, Walther and Russell (2009, p. 329) note the importance of personal agency, using these values to guide our lives and narratives moving forward.

At the very least, this exercise has reminded me that paid sick leave* exists for a reason. But it has also taught me the importance of narrative therapy in determining our personal and professional values; values which will undoubtedly help us navigate the increasingly uncertain future world of work.

* This link takes you to an Australian Unions petition demanding paid sick leave for casual workers impacted by COVID-19, which I urge you to sign.

References

Dulwich Centre Publications 2020a, ‘Michael White archive’, The Dulwich Centre, online, viewed 2 September 2020, <https://dulwichcentre.com.au/michael-white-archive/>.

Dulwich Centre Publications 2020b, ‘Some reflections on the legacies of Michael White: An Australian perspective’, The Dulwich Centre, online, viewed 2 September 2020, <https://dulwichcentre.com.au/michael-white-archive/michael-white-legacies/>.

Dulwich Centre Publications 2020c, ‘What is narrative therapy’, The Dulwich Centre, online, viewed 2 September 2020, <https://dulwichcentre.com.au/michael-white-archive/>.

Carey, M, Walther, S and Russell, S 2009, ‘The absent but implicit: A map to support therapeutic enquiry’, Family Process, vol. 48, no. 3, pp. 319-331.

Freedman, J 2012, ‘Explorations of the absent but implicit’, International Journal of Narrative Therapy & Community Work, no. 4, pp. 1-10. Accessible here.

Freud Museum London 2016, Freud’s theory of Negation, online video, 23 September, Freud Museum London, viewed 2 September 2020, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H3tZOSeeQNo&ab_channel=FreudMuseumLondon>.

Lawlor, L 2019, ‘Jacques Derrida’, in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, EN Zalta (ed.), Stanford University, Stanford. Accessible here.

The Centre for YouthAOD Practice Development, ‘E2. Hearing the client’s story’, YouthAOD Toolbox, online, viewed 2 September 2020, <https://www.youthaodtoolbox.org.au/e2-hearing-clients-story>.

White, M 2000, ‘Re-engaging with history: The absent but implicit’, Reflections on Narrative Practice: Essays and interviews, Dulwich Centre Publications, Adelaide, pp.

–2003, ‘Narrative practice and community assignments’, International Journal of Narrative Therapy & Community Work, no. 2, pp. 17-55.

–2005, ‘Children, trauma and subordinate storyline development’, International Journal of Narrative Therapy & Community Work, no. 3 & 4, pp. 10-21. Accessible here (opens as a PDF download).

Josie!!!! This was absolutely incredible. I love your writing style, especially the “on ____” headings to break it up and keep it relevant. So good, massive high 5!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Isobel, thank you! Such a beautiful message to see this morning, I really appreciate you taking the time to share.

LikeLike